A TASTE OF HOME WITH ILLUSTRATOR BETH WALROND.

YUN interviews Berlin based illustrator, Beth Waldron

(4-5 MINUTE READ)

“I was really into album art when I was younger,” says British illustrator Beth Walrond.

Particularly inspired by the release of Lebanese-British singer Mika’s “punchy, colourful, and blocky” album Life in Cartoon Motion, Walrond was compelled to google what courses you could study in order to get a job creating album art. The first thing to come up was an illustration degree at Falmouth University in Cornwall, and, after visiting the coastal campus for an open day, Walrond’s “heart was set” on attending the Cornish university. So began her journey to becoming the successful freelance illustrator she is today.

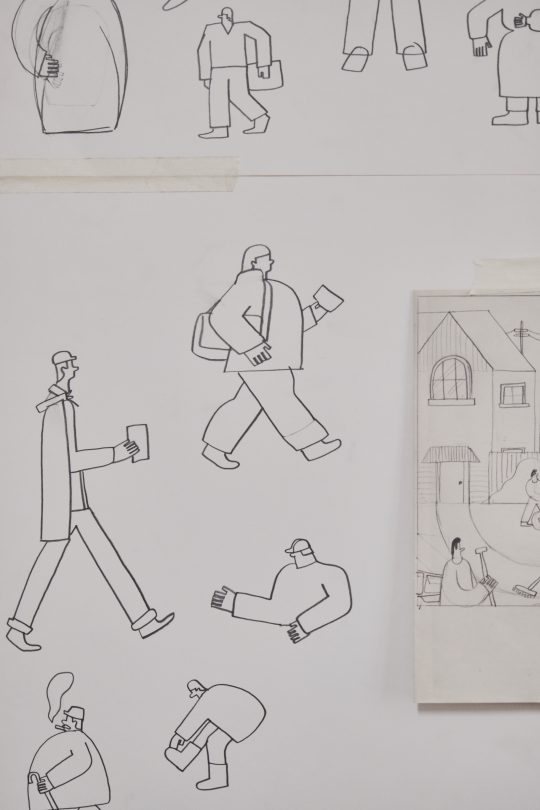

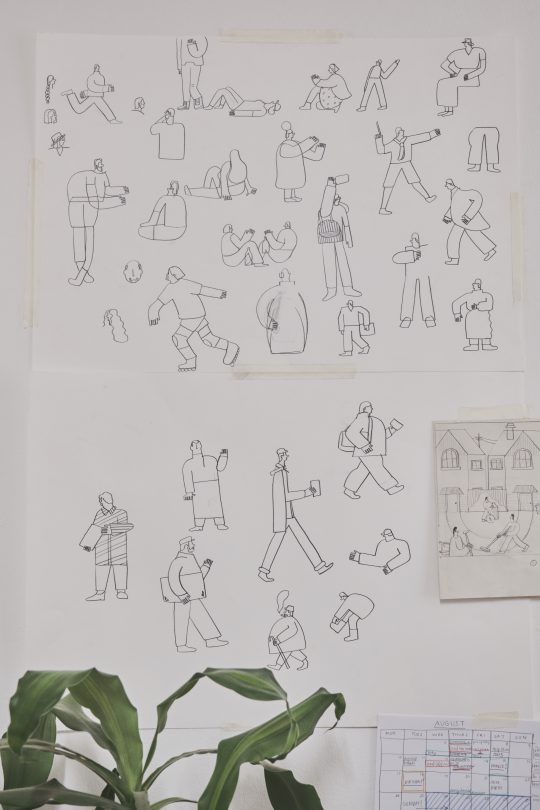

Since graduating from her dream course, Walrond has worked for a variety of publications and clients, including The New York Times, The Guardian, Wired, and The Wall Street Journal to name a few. Producing illustrations in her signature style, with bright colour palettes and chunky-limbed, geometric characters, she translates complex texts into vibrant visuals, summarising editorial content without trying to represent every fact, figure, and minor detail. “I really like working on lots of different things at the same time,” says Walrond, who juggles short editorial projects where you have to “trust your instincts,” with longer advertising projects with strict requirements. “The editorial stuff is particularly fun because you get to learn about things you may never have considered.

You get given articles about random topics that you have to become an expert in for a day.”

Despite having an impressive resume to date, Walrond admits she still gets imposter syndrome when working with high profile publications. “I get really starstruck! I used to just send awful draft sketches to art directors to see if I was going in the right direction. I felt like I needed their approval, or for them to tell me I was doing great every step along the way,” she explains. Now, she’s getting more confident in her abilities, and only sends sketches to clients when they’re in a near-finished state. “In general, I’m also getting more confident with my use of colour,” Walrond adds, describing how she likes to experiment with using limited palettes, selecting five coloured pencils at random and then forcing herself to work with them. “It really helps me to have a distinct idea of what I’m doing.”

Based in Berlin since 2014, Walrond originally moved to the city post graduation to make the most of its low, freelance-friendly rent prices. Now, having lived in the German capital for six years, Walrond says it feels like home. “Every area I’ve lived in or made memories feels really warm in some way,” she explains. “It’s as if you can walk around and remember all the different chapters of your life here.” Currently, Walrond lives on the outskirts of Berlin in Baumschulenweg, which feels like a small, countryside village in comparison to the bustling streets of the city centre.

“I really love going home, but it’s also really nice to spend time at my studio in Kreuzberg and feel immersed in the energy of the city.”

Walrond does, however, at times feel homesick for the U.K., especially as the country faces unprecedented political challenges, such as Brexit and the coronavirus crisis. “I feel very disconnected from it in one way, but also very emotional about it,” she says. “It’s like you’re watching a film play out from a distance. But it also feels like you can see what’s going on more clearly, because you’re not deep within it,” she adds, noting that she feels particularly sad about not being able to see her parents for the foreseeable future due to uncertainty around international travel.

Coronavirus travel restrictions have not only affected Walrond’s personal relationships, but also her creative practice, which is usually greatly influenced by trips abroad. “I feel like my work is stuck at the moment. I just sit at my desk all day long, and I haven’t been able to observe anything new for a while,” she says, noting that some of her favourite locations to visit before the global pandemic included New Zealand and the countries surrounding the Medittereanean Sea due to their vibrant colours.

“I really like places that are busy with people so I can draw the interactions between them.”

Walrond’s fascination with travel was the driving force behind her first book, A Taste of the World, which was published by Little Gestalten last year. Aimed at children, the book comprises 80 pages of brightly illustrated maps revealing the eating habits and cuisines of countries from all over the world. “Food is such an interesting way to get to know a place,” she says. “I thought it would be nice to make a book that opens kids eyes up to the wide variety of cuisines from all around the world, and how they reflect their respective cultures.”

Good food is not just an exciting way to experience different cultures, for Walrond, it’s also a big part of feeling at home. “I cook every day and I spend a lot of time on it. I find that one of the most homely things,” she says. “I even have a garden at my flat now where I grow potatoes, a specific type that my Dad always told me is the best. I made some into chips recently. They were so good and tasted like home. It was really crazy, it was like my memory was triggered by the flavour.”

Walrond notes that expats’ desires to have a taste of home may be one of the main reasons Berlin has such a vibrant gastronomy scene peppered with independent, international restaurants, from Syrian eateries to Turkish doner stands.

“It feels like a lot of people who are originally from the country go to them to reminisce about home, it’s really nice” she says.

But these restaurants are not just for natives— they also allow other nationalities to experience cuisines they may not be able to try otherwise. “I went to a Ghanian restaurant the other day and it was so good. I don’t know if I’ll ever get to go to Ghana, especially with the way travel is now, but it’s really nice to eat something from a place you don’t know much about. Afterwards, you already feel slightly less ignorant. It’s almost as if you can go to loads of different countries without leaving Berlin.”

It is impossible to think about people making new homes for themselves in foreign countries without thinking about the devastating refugee crisis that was at its height during the mid-to-late 2010s. “It was pretty intense here,” says Walrond referencing how Germany pledged to take on 5000,000 refugees annually, a promise that was met by a rise in anti-immigration protests in the country. Amazed by the fact that it was so hard for people escaping from war torn countries to build new lives for themselves in Germany when it had been so easy for her as a British person, Walrond decided to volunteer her time to refugee charities, at first making and serving food at shelters, and later handing out clothes. “I was constantly trying to find something else though because I found it quite difficult. I wasn’t very good at knowing what people needed and I thought that maybe I could be more useful by offering the skills I use in my job,” she says. In the end, after a long internet search, she found and joined Pass the Crayon, a charity offering art and illustration workshops to refugee children in Berlin. “It was so nice to work with the kids, and provide a therapeutic distraction that’s also a great way of integrating them into the city,” she says.

“Art and creativity don’t need language, so even though not everyone at the workshops spoke German, the kids didn’t care. It was very universal.”

Sadly, Walrond hasn’t worked with Pass the Crayon in recent months, their workshops being paused due to coronavirus and the fear of taking it into a refugee shelter. Hopefully, she’ll be able to resume soon, and continue to welcome people into a city that she’s set to call home for the foreseeable future. “I think it happens to most people when they come here. Once you settle in Berlin, you never get round to leaving.”