CHANSOOK CHOI ON MEDIA, ART, SAFE SPACES AND PORTRAYING FEMALE NARRATIVES

In conversation with Korean artist, Chansook Choi

When asked how she first got into art, Chansook Choi jokes that she didn’t have much of a choice.

The daughter of a sculptor and a painter, the Korean native was surrounded by creativity from a young age. “It was natural for me to follow in their footsteps,” she says while sitting in her Prenzlauer Berg studio, citing Tino Sehgal, Anne Imhof, and Rebecca Horn as some of her earliest inspirations.

“They all work with concepts of non materiality, human beings, and movement. They create really great pieces.”

Choi’s admiration of Horn in particular was so strong that it inspired her to move from Korea to the German capital in 2001 with the hope of taking the artist’s class at Berlin’s University of the Arts (UdK). Although this never transpired, Choi did, however, enroll in the institution’s Visual Communications and Media Art undergraduate degree, a decision inspired by seeing films by UdK students shown on screens usually used for advertising in Berlin’s U-bahn network. “I didn’t have much interest in exhibiting in white cube spaces at the time. I wanted to try a different access point, and experiment with film and new media,” she says.

Since completing her bachelor’s degree, Choi has worked as an independent video and media artist exhibiting her work in international institutions including across Germany, Korea, and the U.S. She does admit, however, that transitioning from university to working as a professional in the art industry was tough. “We never really learnt about how to make a living. Many people think artists just need to be talented or naturally gifted, but you also have to have vast amounts of knowledge about practical things like calculating tax, protecting your copyright, and how to earn a sustainable income. It took me a while, but I’m getting there, slowly.”

When she first graduated, Choi mainly focused on producing work that intersected with alternative disciplines such as dance and science.

“Each medium has its own specific language. I really liked trying to combine these complex things and showcase them as part of a performance or media artwork,” she says.

But in 2016, the artist came to a turning point in her practice. “I started really thinking about my background and heritage,” Choi explains, adding that she was particularly interested in her grandmother’s story of travelling from her home country of Japan to Korea to be with Choi’s grandfather, who she had met while he was working as a labourer in Japan. “I decided to work on a project tracing this journey.”

Titled Re move (2017), the work saw Choi record interviews with her grandmother and hundreds of other women from Japan, Germany, and Korea who migrated from their homes after World War II. “I discovered that they all have a very specific way of viewing the world. I would ask them some quite random questions, like ‘what is a ritual,’ for example, and they would answer in really amazing ways. They have this wisdom that comes with maturity. I interviewed some men with similar experiences too, because in the beginning I thought gender wouldn’t make much of a difference. But it’s actually really different when men and women speak. I think it’s important to think about why that is.”

Since Re move, Choi has worked on many other projects that focus on the lives and stories of women. “I’ve recently got married and had a baby. I think this has made me focus on this area even more,” she explains. One such project is Mytikiana (2019), an 18 minute long video installation based on research into Japanese military comfort women: women and girls who volunteered or were forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army in occupied countries and territories—Korea being one—before and during World War II.

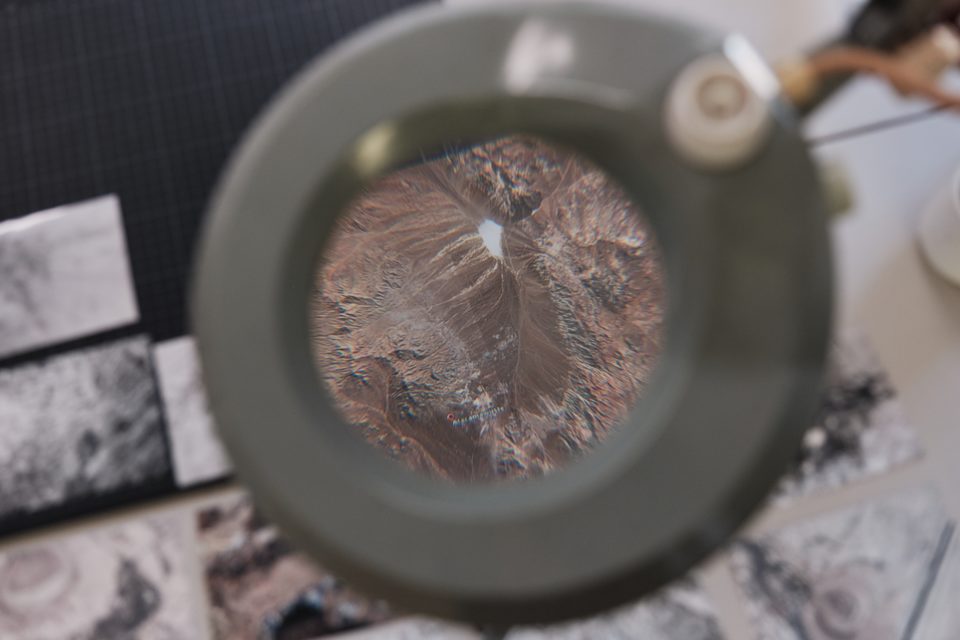

While Choi initially recorded interviews with former comfort women still alive today, she couldn’t get away from the worry that she was objectifying them and their stories, especially considering the amount of times they’d been theatrically portrayed in the media before. It wasn’t until a research group at UdK who were looking into the subject came to Choi that she resumed her research. “At first I said I didn’t want to work on the topic anymore. But then they told me they’d found evidence of around twenty comfort women from Burma, none of whom had shared their stories before. I thought it was very important to think about why they’d decided to stay silent.” As a result, Choi created a film in which three actors portray Burmese comfort women. Delivering text based on the research compiled by the university, films of their faces are accompanied by animations of rotating forms akin to space hardware. “These circulating images reflect how topics such as this one can be seen from different perspectives.”

The topic of comfort women is still a very sensitive subject in Japan and Korea. “I think this situation won’t end until the generation that experienced it passed away,” says Choi. As a result, she sometimes feels like her work on the subject is “not so welcome” in Korea.

“It’s very important to speak about it in an art context. It feels like a safe space to talk about polarised issues.”

Choi is no stranger to creating safe spaces to discuss difficult issues: in 2014, she co-founded NON Berlin—a Berlin-based platform for Asian contemporary art—with Korean architect Ido Shin. “I’ve met a lot of curators who have pigeon holed me as a female, Asian artist. But then, when I’ve been in Korea, I’ve also met people who have told me my work is very German,” she explains. “This got me thinking about what it means to be a German artist, what it means to be a Korean artist, and the intersections between the two. I wanted to make some friends who were thinking about similar topics, and that’s why I started NON Berlin.”

Based alongside Choi’s studio in Prenzlauer Berg, NON Berlin usually hosts shows two to three times per year. This has, however, like every other aspect of Choi’s work and the art industry in general, been disrupted by the global coronavirus crisis. But despite the challenges resulting from the pandemic, Choi believes it has also given her time to ask herself some interesting questions. “I have always been thinking about which will be the winner: the virtual or the real world. I think now, due to COVID-19, the virtual side has won,” she says. “I’m really thinking about how I can use this opportunity to show new work in a digital space.”

While some may think this may be easy for a media artist, Choi argues it’s not that simple. “People think that films can just be translated online. But many of my films are installations that are intended to be shown in specific spaces. Now that can’t happen, I think I’m going to have to change my methods, and make my work conceptually different from the beginning.”